|

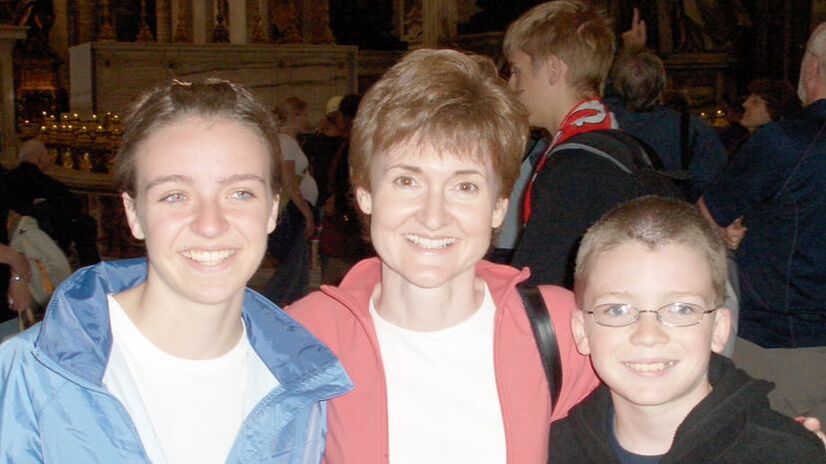

When our kids were ten and 15 we took a family trip to Europe. It felt like a big deal at the time, and looking back on the trip now it was a big deal. At least for us. It was the first time the kids had been outside the US, and we'd all spent months planning and talking about the trip. My husband and I had done a fair amount of international travel for business, and we thought it was important for the kids to have some of those experiences too. Our adventure started in Rome. After flying all night, we landed at the airport where we were to board a train into the city so we could check into our hotel. After retrieving our luggage (another funny story) we went in search of the train. Still a bit groggy and disoriented, we pointed out airport "differences" to our kids, as we all took in the sights and sounds of our surroundings. After only a few minutes we had to stop and regroup. We just couldn't seem to find the train station that the guidebook assured us was right in the airport. This was in 2006, so pre-smart phones, which meant we had translation books and hard copy guidebooks. My husband and I engaged in a bit of intense debate as we tried to determine the best way to find the elusive train station. At this point, our ten year old son, who is never afraid to speak up, suggested that maybe we should head in the direction of the train icon posted on some of the airport signage. My husband and I looked at each other and laughed as we told him, "Good idea!" We then wondered how we'd managed to miss that very obvious clue ourselves. Our belief was that we were the European travel "experts", and we hadn't left much space for the kids to become experts themselves. We hadn't even recognized them as valued members of the "team". That experience, combined with the recognition and observation that many parents (ourselves included) insist on being the experts, leaders, and sometimes even saviors when they interact with their kids, changed the way we traveled as a family from that point on. We recognized that the kids were often as capable as we were, and we gave them opportunities to prove it. We all seem to want our kids to excel in so many areas ... unless we're around. If we're around, we often reserve the role of "expert" for ourselves. It feels so darn good. For us. But what does it do for them?

0 Comments

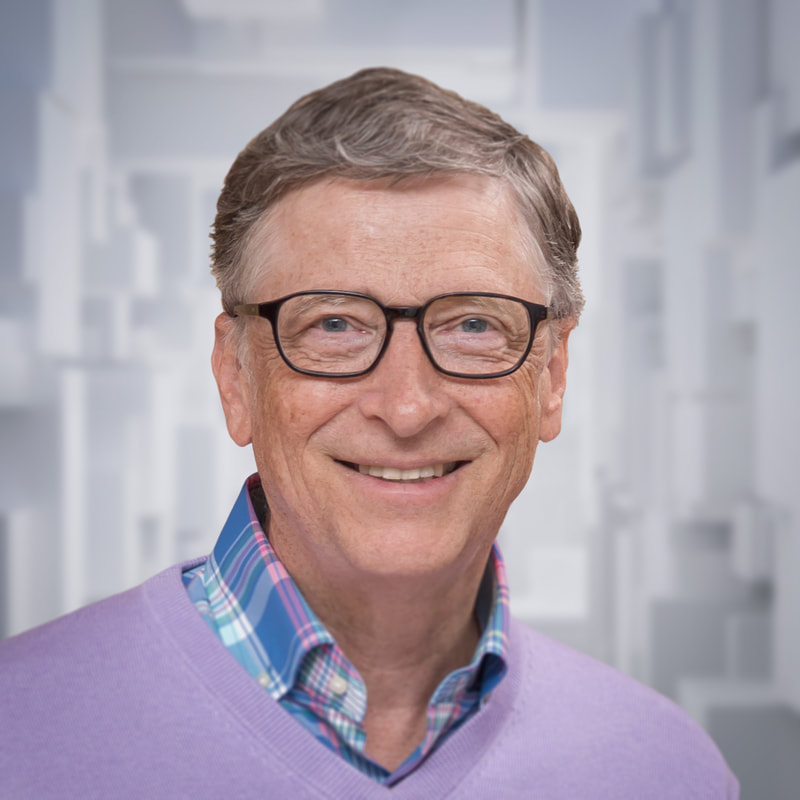

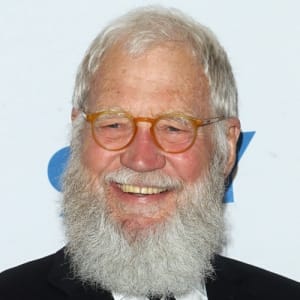

A lesson from from David Letterman's Netflix interview with Melinda Gates Melinda Gates is interviewed by David Letterman in season 2 of his popular Netflix series "Our Next Guest Needs No Introduction". During the interview, she talks about her work in the developing world, the roles of women there, and the realization that even in the US women have not achieved equality in many places. So she asked herself many questions including, "How can we be sure we get equality in our homes? In our community? In our places of work?" David Letterman asked her, "How can we? What is the key there?" Her reply: "I think you have to start in your home." She went on to say that sometimes you have to have uncomfortable conversations in your marriage to make sure that you have equality there. She then goes on to provide an example. When their oldest daughter started preschool, Bill suggested that he should drive their daughter to school two days a week, and he did. Suddenly, a lot more fathers started taking their kids to school too. Apparently when some of the mothers saw that Bill was driving the little girl to school, they went home and said to their husbands, "If Bill Gates can drive his kid, so can you." Never underestimate the power of your actions. You may not be Bill or Melinda Gates, but people notice what you do (and don't) do. You can make a difference.

Related stories:

Submitted by Kathy Haselmaier A number of recent activities have me thinking about an intersting way parents differ, even within tight groups. It seems that some parents encourage their children to try to "fit in" while others encourage them to try to be "different". Most parents want their kids to succeed, but they don't always appear to agree about which paths are most likely to lead to success. I'm thinking that in many cases, our work experiences influence our parenting philosophies. When in come to helping kids develop their identities, some parents appear to strongly encourage their kids to seek out a good group of friends and then find ways to "fit in". In some cases the parents even go to extraordinary lengths to ensure that their children will be accepted by a group by encouraging (or even pushing) them to pursue popular activities such as soccer, choir, or academics. Sometimes the parents go as far as purchasing expensive things like clothes, cars and trips to be sure that the kids "fit in". Then, once the kids are established within a group, the parents encourage them to try to stand-out among that group. Other parents appear to take a different approach. They don't appear to value the trending activities as much and instead encouage their kids to follow an inner calling and/or look for empty spaces to fill be pursuing less popular activities like fencing, origami, or cooking. These parents seem to think that their children are more likely to be successful in this way. Is one way better than the other? Well I certainly have a preference for one of those routes over the other, but maybe that's because it's the best path for my kids. The more I think about it, the more I think we need both kinds of people; those striving to seek commonalities as well as those who want to be different. If everyone was striving to fit in all of the time things could get very boring very quickly. And if everyone wanted to be different, maybe nobody would be different, and we'd devolve into a state of utter chaos. Which kind of parent are you?

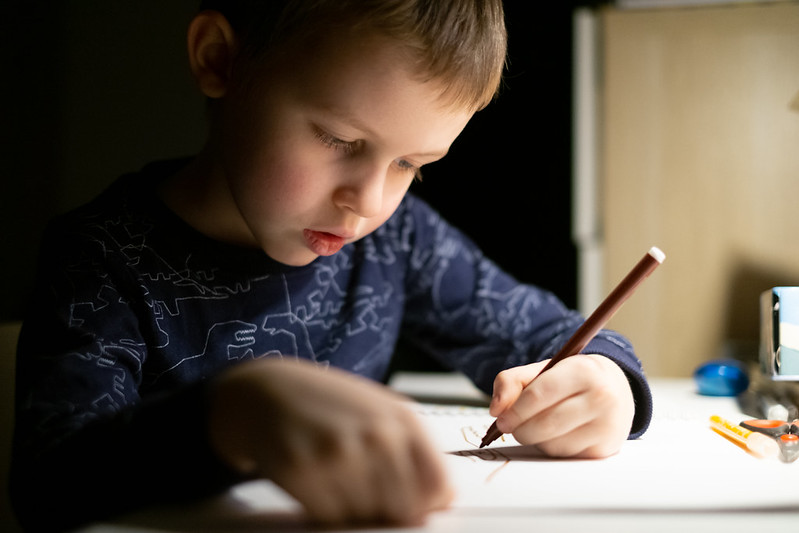

Inspired by a New York Times article by Jessica Bennett What does your child's failure, large or small, imply about you? Many parents, those who pursue careers and those who don't, seem to fear that a child's failure will imply that they aren't parenting well. Think about that; some people think that a child's failure isn't healthy and even go to unusual extremes to help their children avoid failing. This topic caught our attention after reading an article in the New York Times called "On Campus, Failure Is on the Syllabus". It turns out that some students are so unfamiliar with failure that some colleges are offering courses to teach them how to do it. As a working parent, this topic caught me off-guard because failure was an integral part of daily life around our house. While I always produced clean clothes for everyone, they weren't always dry. Homework and lunches were occasionally forgotten. Planes were missed; twice. Test scores weren't always worthy of display on the refrigerator. Vacation activities sometimes proved to be ... not so fun. And managers didn't always heap on the praise. And yet ... we survived. Sometimes we even succeeded. Each of us learned, at least theoretically, that when something doesn't turn out the way you want, you keep on going, try harder next time, and often need to change your behavior to avoid experiencing even more failure in the future. Failure isn't a showstopper, but it is often a signal that change is needed. Many years ago a friend advised, "Let your kids fail on the little stuff when they are little so that they're not learning to deal with failure for the first time when they are older and the stakes are much higher." We took the advice to heart, but have to admit, even today, that watching anyone you care about fail is not easy. And it's not fun. Sometimes we failed when it came to teaching failure. "Good parents" let their kids fail; they don't swoop in, solve problems that children could solve for themselves, and then declare themselves the heroes in their family stories. Instead, they encourage children to resolve their own failures, and they allow their children to feel the satisfaction and experience the increased self-confidence that those failure experiences produce. They let their children become the heroes of their own stories, and they teach them that struggle can be valuable. They understand that parents should attempt to keep their children safe, but that most failures don't compromise safety. For all parents, and especially working parents, these realizations can be freeing. When we make room for failure, we spend less time doing and more time watching, supporting, and encouraging. As Retired USAF Colonel Gregory H. Johnson said at Michigan Tech's spring commencement ceremony recently, "Failure's not only an option, it's a requirement for succeeding in life." Related story:

Working Parent Stories often mentions the fact that kids learn from parents and the kids of working parents learn unique and valuable lessons. Having just finished reading the book Educated by Tara Westover, it seems safe to claim that she learned some really unique lessons from her working parents. And many of them have turned out to be surprisingly valuable and definitely thought-provoking. We're late to the party in terms of reviewing and praising this book given that Barack Obama included it on his 2018 Summer Reading List and Bill Gates recently gushed about it too. With that said, in addition to being a compelling memoir, it gives parents a lot to think about in terms of what aspects of parenting and education help a child the most. Educated is a real page-turner* that will leave you thinking and thinking and thinking some more about what you've read, what it means to be a "good" parent, and what opportunities and responsibilities you provide for your children. After you finish the book, we recommend listening to interviews with the author posted on YouTube (like this one) to gain even more insight into her story. * We actually listened to the audio version

A movie review We enjoyed the CNN documentary RGB enough to conclude that we wanted to see "On the Basis of Sex" too, the "inspired by a true story" movie about events that occurred duing Ruth Bader Ginsburg's education and early career. And we're glad that we did because it provided a different view into Judge Ginsburg's history. (One, we should note, that is somewhat fictionalized. You can check the facts vs. fiction online.) Not long ago, I attended a class called "Understanding myself from a cultural perspective". One of the most memorable things the instructor told us is that an outsider can't become a member of a group unless he or she has an insider advocate. In addition to being a thought-provoking claim, it got me thinking about responsibility; specifically, what responsibility do I have to help others who are on the outside? This movie, and other stories I've read about Judge Ginsburg, highlight the fact that after finishing two years of Harvard Law School and then graduating from Columbia Law School (where she tied for first in her class), RBG couldn't find an NYC law firm that was willing to hire her. That's hard to believe in 2019, but apparently it really happened. Ruth and Marty both worked while raising their two children; Ruth started out as a college professor and Marty spent his career as a tax attorney. It's well known that Marty was the family cook long before many men assumed such roles. Their successes appear to be linked in many ways. Thankfully for Ruth, and all women really, her husband, Marty, remained convinced that she should continue to push the legal system until she found a crack; a way to practice law instead of just teaching others about it. It's an example of a person on the inside advocating for a person on the outside. And it leaves us wondering, is there a person or people who are deserving of our advocacy?

Pointer to an interesting HBR article about working parents If you spend time wondering how your career and/or your spouse's career might affect your kids, you'll want to read this HBR article: How Our Careers Affect Our Children by Stewart D. Friedman. Here are just a few of the interesting insights provided by studies outlined in this relatlvely short article:

Pointer to short video about the value of the roles we model People work for many reasons. We often assume that people work to support their families which is often true. But how often do you stop to think about how your work, and the example it sets, benefits your children beyond putting food on the table and a roof over their heads? Kathleen McGinn, a Harvard Business School professor, explains how our careers help our child in this short video (2:26 min).

Related stories:

Pointer to a Forbes article by Mary Beth Ferrante Yesterday Forbes published a great article called How To Survive A Two Breadwinner Household. We love the article because it promotes many of the same ideas we promote and aligns with many of the topics we've covered recently including the following (and many more):

Thank you, MaryBeth Ferrante, for helping other dual income couples recognize the challenges so we can be sure our families thrive and we contribute to a brighter future in so many ways.

Inspired by an article in TIME magazine Becoming a Stay at Home Dad (SAHD) might feel like the right move for some men. But even if your partner is on-board and ready to become the sole financial contributor within the family, a decision to leave the workforce, even for just a few years, may set your career back in enough ways that you are likely to regret the decision down the road (assuming you think you'll want to reenter the workforce in the future). Last month we wrote about the financial downside to career breaks in the story Do The Math. Later we came across an article in TIME magazine that described other, greater risks, specifically experienced when a man leaves his job to care for his family for an extended period of time. The article, Don't Let Your Husband Be a Stay-At-Home Dad, outlines many of the risks associated with leaving the workforce temporarily and states, "Research suggests the penalty may even be greater for men who temporarily exit the workforce." Every family is different and there is no single career or parenting model that works for every situation. Each of us needs to do what we think is best given our unique situations. The Time article reminds us that there are ramifications to every decision we make, just like we outlined in another recent story, Choices and Consequences.

|

The StoriesArchives

March 2022

Categories

All

|

Photos from barnimages.com, marcoverch, truewonder, donnierayjones, marcoverch, shixart1985, Gustavo Devito, edenpictures, nan palmero, quapan, The Pumpkin Theory, bark, opassande, Semtrio, Ivan Radic (CC BY 2.0), verchmarco (CC BY 2.0), Didriks, shawnzrossi, shixart1985 (CC BY 2.0), madprime, marksmorton, CT Arzneimittel GmbH, NwongPR, franchiseopportunitiesphotos, anotherlunch.com, jdlasica, wuestenigel, Frinthy, romanboed, Doris Tichelaar, quinn.anya, A_Peach, VisitLakeland, MEDION Pressestelle, Darren Wilkinson, bratislavskysamospravnykraj, Anthony Quintano, Danielle Scott, pockethifi, Bridgette Rehg, Martin Pettitt, PersonalCreations.com, wuestenigel, Thad Zajdowicz, archer10 (Dennis) 139M Views, Infomastern, beltz6, The National Guard, futurestreet, daveynin, OIST (Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology), Rinet IT, shixart1985, mikecogh, JeepersMedia, Ryan Polei | www.ryanpolei.com, Jake.Christopher., aleksandrajovovich, thepeachpeddler, wwward0, flossyflotsam, Got Credit, Senado Federal, Corvair Owner, lookcatalog, moodboardphotography, dejankrsmanovic, Carine fel, ElleFlorio, {Guerrilla Futures | Jason Tester}, greg westfall., Arlington County, mariaronnaluna, quinn.anya, wuestenigel, Tayloright, insatiablemunch, MrJamesBaker, Scorius, Alan Light, Monkey Mash Button, www.audio-luci-store.it, wohlford, Vivian Chen [陳培雯], okchomeseller, BoldContent, Ivan Radic, verchmarco, donnierayjones, Czar Hey, US Department of Education, Andrew Milligan Sumo, Michel Curi, anotherlunch.com, ProFlowers.com, Cultural viewpoints from around the world, alubavin, yourbestdigs, Rod Waddington, Tayloright, Wonder woman0731, yourbestdigs, donald judge, Thomas Leth-Olsen, Infinity Studio, shixart1985, wuestenigel, francesbean, Roger Blackwell, MrJamesBaker, Luca Nebuloni, MFer Photography, erinw519, boellstiftung, North Carolina National Guard, A m o r e Caterina, MrJamesBaker, bellaellaboutique, Free For Commercial Use (FFC), Prayitno / Thank you for (12 millions +) view, wuestenigel, Matt From London, MadFishDigital, Kompentenzzentrum Frau und Beruf, mikecogh, CreditDebitPro, marciadotcom, Mr.Sai, _steffen

RSS Feed

RSS Feed